Dawn is yet to break, the sky hangs dark and heavy. Last night’s mist is now a powdery dusting of snow on the moss and ferns. I’m hurrying towards the kitchen where warmth awaits. Olive-backed pipits huddled on a bare tree must wait patiently for the sun.

In the kitchen, Shibu, is slicing some firewood into strips with his sharp dao. This is the tinder bought from the market and burns brightly with an oily fragrance. The heavier logs, collected from the forest upslope are shoved into the thick cast iron bokhari (fireplace), and two grey cats, scramble out of last night’s embers.

The pipes are still frozen solid, but someone was sensible enough to collect water last night in a bucket. The fireplace doubles up as a hot grill and soon we have smoke-flavored water boiling for coffee. The grey cats now slide against the hot iron.

I hear a slurred trill and step outside. My binoculars reveal a medium-sized brown bird rummaging in the undergrowth. It hops on the low bushes and is joined by a few more. My mind is racing. This is obviously a laughing thrush and the white streaking on the head and belly mark this out to be a Bhutan Laughingthrush. A tingle of excitement washes over me. This is what we birders call a “lifer”. A bird species that I had not seen before. Birders care a lot about “lifers”. I can now tick off another bird in the field guide, an act that is sacred and treasured.

I am in western Arunachal Pradesh, in the Eaglenest sanctuary and Bhutan is probably still a hundred kilometers away (as the laughing thrush flies), but the birds don’t seem to care about pesky international boundaries. The olive-backed pipits have now descended to the ground and are inspecting the cold grass, their tails bobbing as they warm up. My binoculars reveal more. There is a male dark-breasted rosefinch, its throat and crown a dark vermilion. Rufous-breasted accentors with striking orange eyebrows have also descended to these altitudes in the winter.

A hill partridge starts calling from the slopes above, its long whistle beckoning me, but these partridges remain tantalizingly out of sight.

Lama camp is now firmly established on the bird-watcher’s pilgrim trail. When China, swallowed up Tibet, the Dalai Lama, fled down the mountains and passed through apparently on a dzo (a domesticated yak) in 1959, with the Chinese army hot on his heels. Now there is a large army base in the valley below at Tenga and the green roofs of the barracks are visible on a clear day. The army, bruised from the Chinese excursions would carve out a rough track that runs through the preserve, keen to bring the upper reaches of Arunachal Pradesh, closer to the plains of Assam. As it so often happens, in the decades that followed things dawdled along. The road fell into disuse and a few small hamlets took root centered around farming and logging out the timber.

Things would have taken a different course, if not for the discovery of a bird new to science by Ramana Athreya, an astronomer who spotted an unusual-looking small babbler while on a vacation in 1995 and named it Bugun Liocchicla after due scientific diligence in 2006, in honor of the native tribe, the Buguns, who live around the hamlets. Athreya would also partner with the Buguns and organize the first-ever bird tour. The northeast Himalayas could be trusted to provide exotic birds and the Bugun Liochicla had the extra charm of not even being included in the field guides at that time. The Buguns were initially surprised that so many city dwellers were willing to rough it out in the wet and cold tents to see the birds but appreciated the economic mini-boom.

Meanwhile, the Indian army had other plans. They wanted to upgrade the rough dirt road that turned to slush and boulders during the rains into something more permanent. Of course, some trees would be cut and hillsides blasted to better scare the Chinese. The Bugun liochicla would be lost to science soon after its discovery. The Buguns, who now identified with the new bird, so cleverly named after them and keenly aware of the economic benefits that it entailed banded together and stopped any further road widening activities.

Today, birdwatchers traverse this trail, first cleared out by the army that so conveniently cuts through over 3000 meters of altitude, with the tropical moist bamboo giving way to broadleaved evergreen and pine forests. In all over 600 species of birds occupy this diverse habitat, roughly 60 percent of India’s avifauna packed into a small sparsely populated region.

The forest department mostly stays out of the way. They run a small checkpost, but I never see anyone manning it. Large tracts of Eaglenest is I think privately owned forest land that belongs to the Buguns. The entrepreneurs who run the camps pay a tax to the Bugun committee and the birds live a mostly well-protected life. Yay, Capitalism!

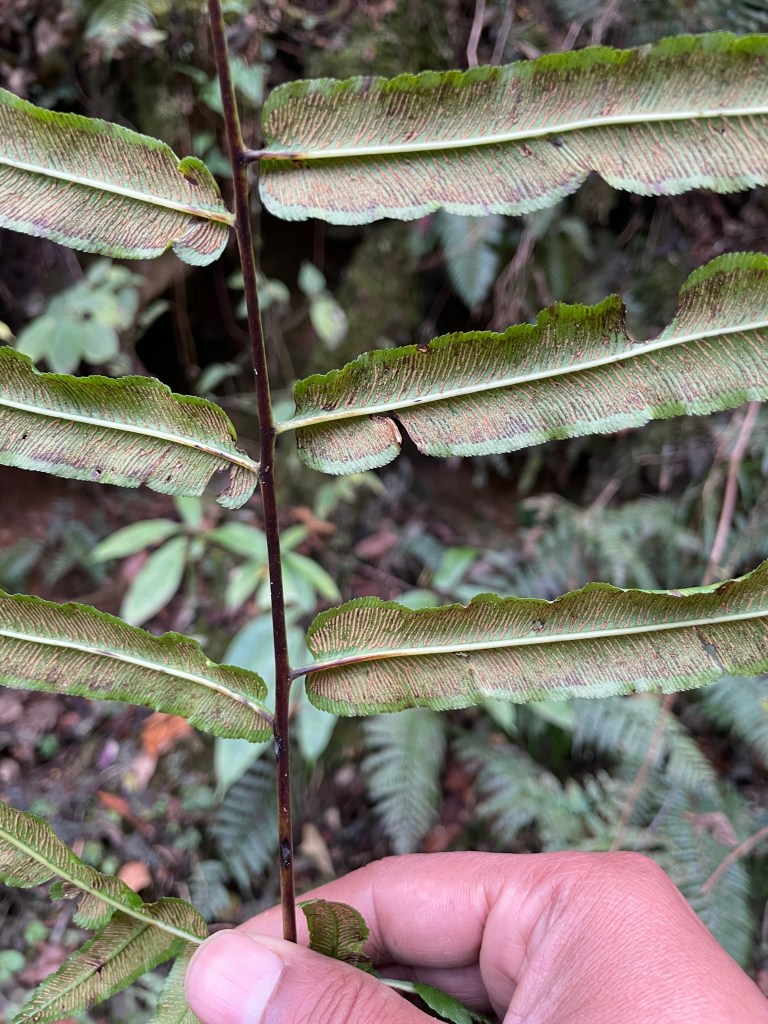

I set off after my morning coffee, walking up from Lama camp. A nice easy hike along the evocatively named tragopanda trail through moss-laden oaks and still-frozen ferns reveals beautiful sibias, sallying forth in search of winged insects. A broad black eye stripe gives them a bandit-like charm.

A pair of white-tailed nuthatches, small almost tailless birds, creep among the epiphytes that drape over a maple tree, gleaning insects from the mid-canopy. Trametes, a woody mushroom grows in large clusters on a still alive tree trunk. It’s a shelf of crisp turkey tails.

On a fallen log, there is a large twisting scat. Hair fibers are distinctly visible. Probably the digested remains of an unfortunate barking deer. The large size and obvious carnivory look lead to juicy speculation. A clouded leopard perhaps? Later I would meet some field researchers who laid camera traps here to study the large cats and they surmise it’s from an Asian golden cat, a large leopard-like feline with a pale dusky coat, rarely seen.

I hear a high-pitched cheep tcheep call and leave the trail and plunge foot first into a thorny thicket of some sort. A crimson-breasted woodpecker is drumming softly on a tree. I get bizarrely close and am almost at eye level. The woodpecker spirals around the tree, often reversing for a better angle. Just then I see a tick walking meaningfully on my pants, and I quickly turn tail and scramble back to the main trail.

On my way back to the camp, I stumble into a flock of birds. The yuhinas are out, the threesome of whiskered, stripe-throated and white-naped. A few yellow-browed tits and green-backed tits mix in. And there is a large assembly of orange-bellied fulvettas. The last one gave me a bit of trouble. I had to leaf through my field guide with frozen fingers to satisfy myself completely. This is a mixed hunting party or mixed flock as the serious-minded birders call it, a specialty of tropical forests.

It’s rather unusual in the animal world, for species that compete for the same resources to all hang out together. The hypothesis is that there is statistical safety in numbers and a predatory owl is much more likely to eat one of your mates instead of you. The other benefit of joining mixed flocks is that the horde of birds that descend in a wave, drive out insects, much like hunters who beat the jungle. There is some inter-species learning going on too, with the birds learning from one another about good and bad spots for grub.

The trick to observing a mixed flock is to just stay still and calmly focus through your binoculars. Remember the flock wants to make it difficult for a predator to single out one particular individual, and so keeps twisting and turning. It’s frustrating for a birder, who wants to get a clear look to satisfy identification demands. Stay still and the birds get close, surrounding you in a whirr of fluttering wings. Just as quickly as they arrive the flock moves along and the forest is quiet again.

Lunch awaits at the camp. Dileep, the nepali-assamese cook turns out to be a culinary savant. There is delicious dal, stirred cauliflowers, rice, and papad. One evening, he even turns out a delicious pizza, steamed in a momo (dumpling) pot. When the occasion demands, he opens a tin of gulab jamuns to finish off dinner He is also constantly cold and spends most of his time around the bokhari, complaining about the lack of diversity in the ingredients that have to be hauled up here. He says he is tired of cooking dal and reminisces about his days as a chef in a big restaurant in the city of mysore, far away in the plains.

Over many hours spent around the fireplace, with me taking down bird notes for the day, Dileep rambles on. Running away from home on a southbound train, driving ambulances, collecting tips for more unsavory tasks, and smashing speakers to stir up communal tensions while restoring silence in the early mornings. It seems like he has done it all. Now he sports a shock of red hair, done for a mere 200 rupees in the valley below, but mostly covered up by an Indian army wollen cap.

The grey cats look meaningfully as I savor my lunch. I learn that they occasionally supplement their rice and dal diet with more exotic fare. A finch or a pipit makes for a welcome change. One of the cats has a singed ear from getting too close to the fire and apparently loves to irritate the crew by bouncing on the tin roof just as they are about to fall asleep.

I get to know a bit more about the rest. Shibu and Shyam are two young Nepali lads from the small hamlet of Ramalingam, just below. Their tasks right now are to build a kitchen outhouse and haul firewood. Shyam is a keen gamer and takes frequent breaks to play a first-person shooter game on his phone. Much to the disapproval of Arjun Thapa , a single dad turned grandad who is the most senior and has been at Lama camp the longest.

A few cabins are being built for birding tourists who seek a bit more comfort. Khandu and his son Motu (who is actually a fit young lad) wield chainsaws and hammers at the roof. They will return to their homes once they finish, growing cauliflower in the spring. Khandu and his son are Bugun, but they all speak Nepali. Khandu carries a magnificent-looking khukri, in a battered sheath and spends his evenings watching Nepali movies on YouTube. His son brings out a guitar in the evenings and the youngsters gather around another Bokhari. There is a certain confidence in the youth here. You will not see construction workers from the grimy plains strum a guitar after the day’s work is done.

My usual routine is to head out after lunch on another short birding walk before the fog sets in. Brown and rufous-headed Parrotbills, Great barbets and even more yuhinas. A barking deer bellows and its call reverberates in the jungle. By mid-afternoon, clouds creep in and soon everything is a slightly damp and cold mist. On my walk back to the camp, I am startled by two large horned bovines walking in the gloom. Initially, I think it’s the Gaur (or Indian bison), but a closer look reveals a large white patch on one. These are the Mithun, a domesticated version of the Gaur. I let them pass with bated breath.

Bred solely for ceremonial needs, the Mithuns have free reign and spend days grazing in the wilds before returning back to their sheds. Then they must be fed quantities of salt and I would get to hear the shrill bellowing horn that their owners would blow to herd them back home. A grown Mithun can cost upwards of a hundred thousand rupees, and a rich bugun makes a generous gift of Mithuns when getting married. Slaughtered during ceremonial feasts, they roam the jungles unmolested at other times. The Buguns in the camp would good-naturedly rib the Nepali Hindus about eating Mithuns.

I learn that the Buguns have taken to marrying Nepali women, and it’s not unusual to have a cousin who is Buddhist, a Christian mother, and a Hindu mate. A mixed flock of humans.

On a bright sunny day, I walk on the tarred road that leads below Lama camp. A loose flock of Great barbets hoot loudly. And then I see a rarity. A yellow-rumped honeyguide, a medium-sized thick-billed bird that usually feeds on beeswax but is today clumsily sallying forth for insects. I get a nice long look.

On my walk down, I see a parked minivan and meet another fellow birder. It’s been several days in the camp, without anyone showing up and I am glad to meet a fellow city dweller. He has a large telephoto lens and is accompanied by a bird guide who is playing the call of the collared owlet in a loop on a Bluetooth speaker. A scarlet-breasted flowerpecker draws closer and quivers it’s wings. I learn that the call of the owlet, a predatory bird, draws out other birds, who indulge in threatening displays to scare away the perceived predator. The photographer gets some very good close-ups and I’m left thinking about the whole episode.

I have never been on an organized bird tour and something about birding this way is aesthetically troublesome to me. The research on whether the use of playback (playing bird calls) affects birds is interesting. Of course, it changes their behavior, and otherwise shy and difficult to see birds make bold appearances. The guides would not use it if it did not work. Does it change breeding ranges, when a bird mistakenly believes there is another competing male in the vicinity or stress the bird into responding to a fake owlet? The consensus is a weak yes.

What it does do is leave behind a guaranteed stream of satisfied birdwatchers and photographers who spend good money on guides and the eco-tourism wheel spins along. I am also amused at my reaction. Usually, I am happy to explain most things as demand, supply, the inevitable economic markets, and such practicalities. But birding seems to bring out the sentimental side in me.

I proceed downhill and it gets noticeably warmer. I am heading to what once used to be a small farming settlement that grew potatoes. Aloobari it (Aloo is a potato in hindi) used to be called then. The story is that the farmers moved out on their own accord, with the promise that ecotourism would bring better rewards than a few potatoes. This disturbed and degraded hillside is the preferred habitat of the much sought-after Bugun Liochicla.

No such luck for me, but I see plenty of other birds. A showy yellow-bellied fantail spreads its tail feathers and prances on a bush. A blue-fronted redstart seems to follow me and I even see some of the nuthatches feeding on low shrubs instead of the canopy. The field guide, reassuringly does have this titbit and I am glad I get to see this. After a few days, without a shower and being constantly jacketed, I take off my shirt and enjoy the sun in Aloobari.

The next day, I would again repeat my transect, but this time I do get extremely lucky. A Blyth’s tragopan, a large and stout pheasant, red and speckled brown crosses the trail just ahead of me and I get a fleeting glimpse. This is a special “lifer”.

I spend a total here of five nights at Lama camp and add substantially to my list of “lifers”. There is a certain vanity in doing it the hard way, without speakers and guides to point out the birds.

I do have immense respect for the local guides, one of whom I get to know better later on. He started out as a cook in the kitchen and is now one of the most sought-after guides in the region. His dream is to see a thousand bird species that call India home and has already seen seven hundred in Arunachal Pradesh alone. He has intimate knowledge of every individual bird and their exact current whereabouts, tracking their altitudinal migrations as the seasons change.

It’s time to move on from Lama. My next destination is Bompu camp, which is at a lower altitude (1950 meters) and promises a different mix of species. I have arranged to hitch a ride with the pickup truck as it makes its weekly trip, with supplies from the market at Tenga. But plans change. The pickup truck breaks down, but Angu the entrepreneur who runs Bompu gets his crew and me onto the next available ride. It’s with Umesh Srinivasan, a researcher who has studied the birds here for more than a decade. It’s a lucky break for me. Umesh sir as he is called in these parts, speaks very good Nepali and gets along famously with the locals.

Bompu is 35 kilometers away and before we can descend, we must climb up to Eaglenest Pass. The track is now dusted with snow and Angu’s kitchen staff are delighted to film the drifting snow from the relative comfort of the bouncing pickup. We cut through waterfalls and are on the lookout for elephants.

We arrive at Bompu and everything is enveloped in a mist. Bompu used to be a logging camp back in the day and now there is a cluster of large tents and a semi-permanent kitchen. The elephants wouldn’t let anything stand for too long and frequently smash stuff that they don’t approve of.

I head out for a short walk, but the mist has quietened the birds. Copious amounts of elephant dung line the trail and I hear that these elephants are moving up from the plains of Assam. Firecrackers don’t deter them and Bompu camp is shut down during the monsoon, left to the rains, leeches, and elephants. Everything must be rebuilt when the season starts in October.

Compared to Lama, the evening’s dinner is pedestrian. There is a large contingent of bird biologists from America and they are on a birding blitz, racking up hundreds of species in the course of a few days. They arrive in two large jeeps, an old monk bottle of rum and have the services of one of the best guides. We gather around the fire, I enjoy conversing with them and learning a bit more about what professional bird biologists do. On this trip, they claim that their guide uses playback judiciously. I learn about the stresses of birding in a large group. Apparently, there is panic when the guide points out a new species and everyone wants to get a look.

After the rather un-satisfying dinner of fried noodles and limp momos, I hear someone strumming a guitar. I head over in the darkness to the independent camp run by Umesh’s field staff. Umesh is strumming the guitar and pork is sizzling in a cauldron on the open fire. Strips of pork are getting smoked for the morrow. The pickup truck that I rode in brought these delicacies.

The researchers have decidedly better dinner and I am happy to partake. I am introduced to Bharath, Nogte, Pema, and Kanchi, young men and women from the hamlet of Ramalingam who gather field data and run the camp. There is also a visiting researcher who is studying how the strikingly colored green-tailed sunbird gets its iridescence.

Umesh is keen to emphasize that he studies birds and is not a birdwatcher. I learn about how climate change is affecting the mix of birds. They are moving upwards, seeking cooler climates to breed, and might soon run out of room. These mountains only go on for about 3500 meters. Umesh and his team have been mist-netting and ringing birds for a long time. They weigh each bird that gets trapped in the nets and ring it. The birds continue and some get trapped again at a different net. This data collected over the years by the local staff paints a picture of how birds that shift their ranges to once-logged forests generally weigh less and perform poorly as compared to the ones that moved into primary forests.

I am woken up at 4 am by the two jeeps revving to get warmed up. The flock of American biologists is on the move and they have ambitions of shining a torchlight on the nocturnal Hodgson’s frogmouth. I chat with Bikram, another lad from Ramalingam who keeps the kitchen organized. He is an aspiring birder and is saving up money to buy a Bluetooth-enabled speaker and a laser pointer to better help the city-birders find their catch. Birding guides here are what AI researchers are in the cities. Everyone wants to join the gravy train.

On my morning walk today, I encounter some very bold Kaleej pheasants. Two richly black males with a crest and a red eye patch, peck at the ground along with a brown barred female. They strut along the trail and don’t seem to mind me at all. A flock of grey-chinned minivets feed on the canopy above. The ferns here are wet and truly large.

A nice walk up through bamboo, reveals colorful gingers and a red fruit called the Indrayan, which birds and humans alike savor. A mixed flock descends. This one is comprised of several dozen yellow-throated fulvettas, a few rufous-capped babblers, and a solitary golden babbler. The fulvettas, are foraging manically low on the ferns and soon the giant ferns are quivering with the birds hidden from view. A few emerge every now and then and I stay still. Some of the fulvettas are ringed, with yellow, silver and red bands. Netted by the researchers and merrily on their way now. Soon the fulvettas are flying a few feet away from me and some close in to inspect my boots. The babblers are higher up and show more respect for the human. It turns out that a mixed flock has leaders and followers too. The nuclear species here is the rufous-capped babbler and somehow it holds the flock together. The golden babbler is the most spectacular. Overhead there are umpteen warblers black-faced and grey chinned, all part of the flock.

These are the moments to savor from Eaglenest. A few days later, I ride back in Angu’s pickup truck (now repaired) and pass through Lama camp, where all is still, and am back to Tenga. We pass the military barracks and I wait alongside the main road. The eyes take a while to get used to all the people and hubbub. A few hours later I am in the plains and a uniform griminess beckons.

Yes these places are magically, if one is asked to get past the basic amenities. Glad you guys explored them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A great pleasure to read your blog: a nice change too from the dry accounts of birding trips which are the norm, punctuated by excited exclamation marks when target birds are seen. And so good to hear about the staff who make these trips possible.

LikeLike

Thank you for reading and your kind words ! I guess I am an old school birder 😉 . Cheers – Satya

LikeLike

It always feels odd to come back to the “normal”

LikeLike