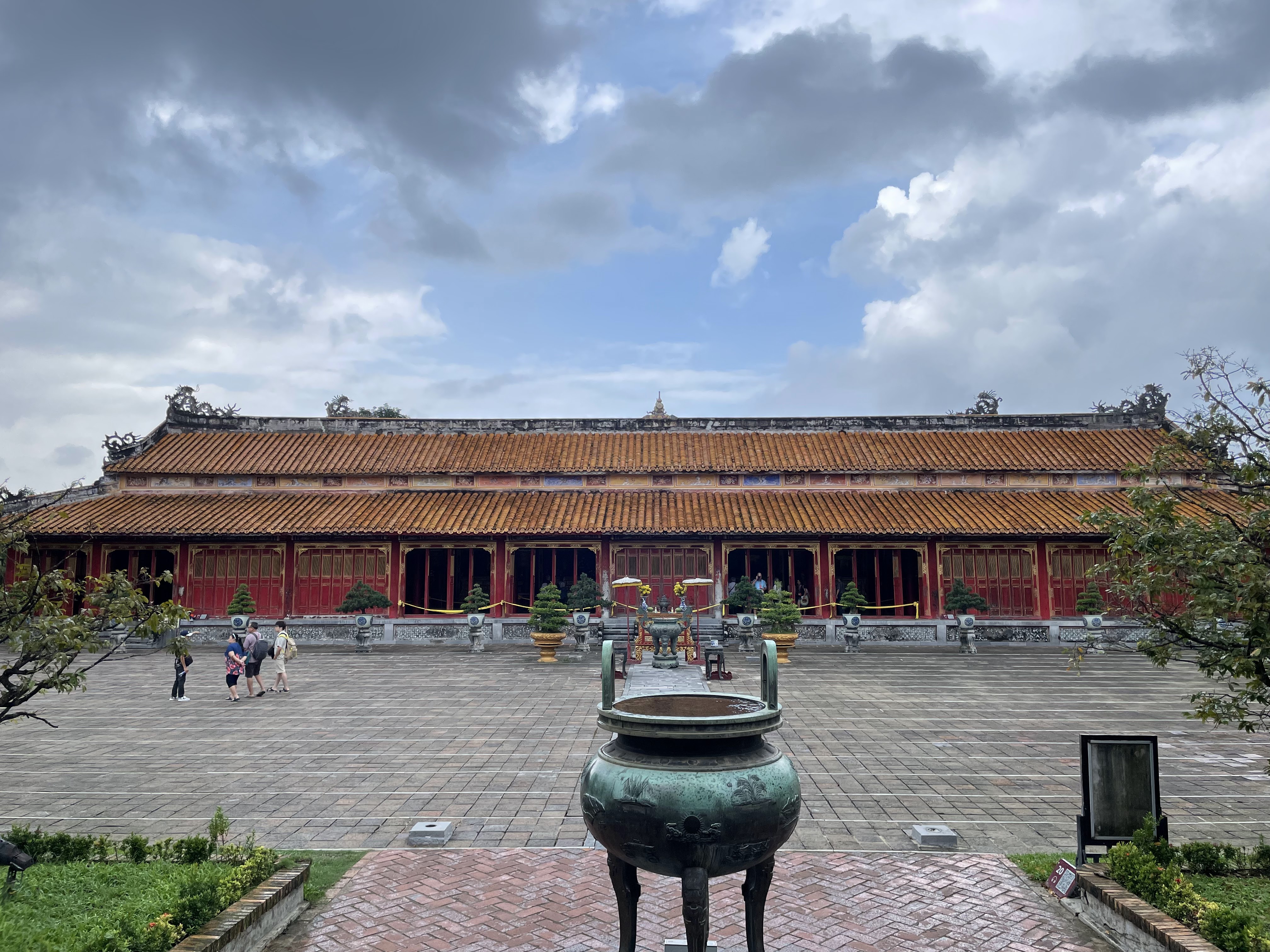

Hue appears to be a sedate yet quirky town, its relatively new past and present jostling together in good contrast. Built in 1803 the citadel and imperial city within it, house the mansions, shrines, and gardens of the Nguyen dynasty. Peppered with green porcelain roofed pagodas, floral tiled floors, and imposing courtyards the imperial city is scenic. Beautifully crafted, massive bronze cauldrons brimming with water reflect the fiery blue sky in the courtyards in a confluence of heaven and earth.

It’s Halloween and all the cafes (and there is one every time you trip on the pavement) are sporting black decorations and battery-lit plastic candles. The coffee is, as usual, impeccable but being a sugarless tea drinker I am left in the deep. How many ever assurances are given that a beverage contains no sugar, I learn that it simply means that the barista hasn’t added any ‘more’ into it but that the premix already has enough for a horse. So I sit and enviously watch everyone drink coffee with condensed milk, or even an egg(Yes! Egg coffee)! Vietnam has crazy coffee I tell you. And every evening I indulged in one delicious cuppa of cappuccino which they made marvelously well with no sugar.

We were in Hue to meet our dear friend Beetho who left Vietnam as a two-year-old and is visiting after decades to see the country but most importantly to visit Hue, where her parents and family were from. We leave on a cold, cloudy morning and our car takes almost an hour to leave the city behind and go out into the suburbs and then the open fields. Ahead, bluish-gray mountains loom festooned with clouds on their pinnacles.

At a nondescript junction, the taxi driver talks into the phone in very quick Vietnamese and takes a left turn. We drive into a village full of small quiet houses, chickens running around and dogs lazing under trees.

We are greeted by an elderly man dressed in jeans and a long-sleeved shirt. He sports a lovely beard and long tresses tied in a ponytail. He zooms ahead on his two-wheeler and shows us the house. We park the car next to a beautiful stretch of the Truoi River where men are fishing on small floating wooden piers.

Ensconced by a small orchard the house looms behind, small but stately with blue walls and a slanting tiled roof. Walking up the pathway we are greeted by two women who are all smiles and bows. Everyone seems to know why our friend is here.

As soon as we step into the central part of the house we are amidst the family altar. A raised platform is arranged with the photographs of all the family members who have passed on and vases of incense stand before their countenances.

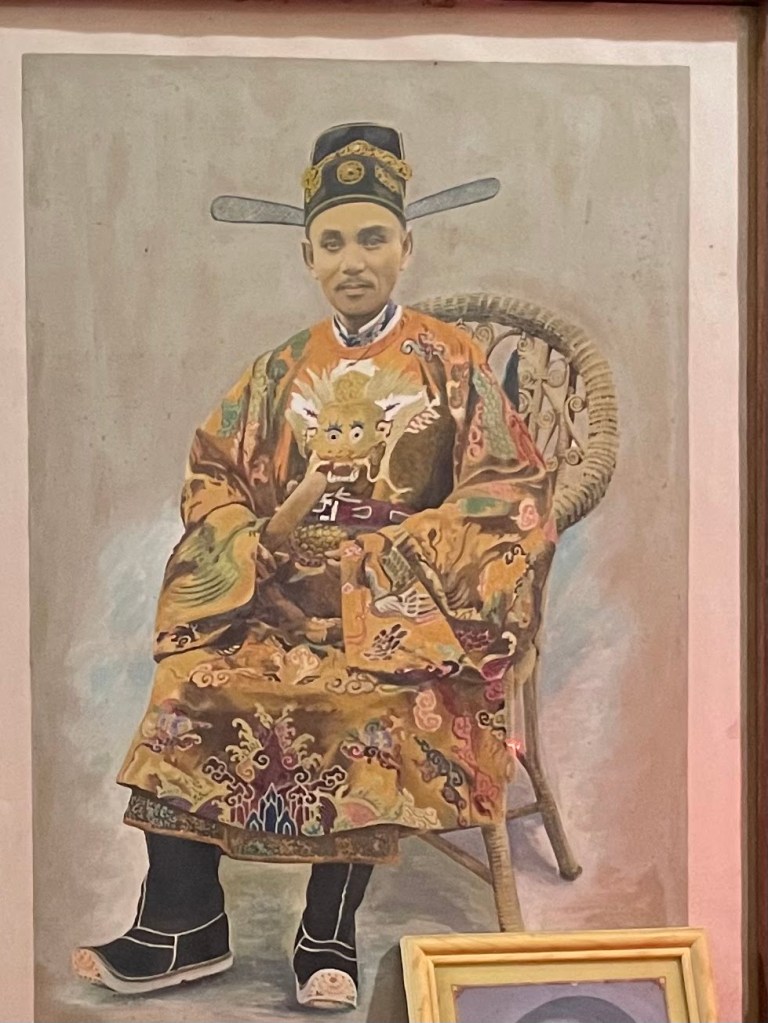

Prominently displayed is a large framed photograph of Beetho’s grandfather. This used to be his house in the early 1900s. He was an excellent mathematician and had aced a tough examination to become a Mandarin. Mandarins were important officials in the imperial court and Beetho’s grandfather served under Khai Dinh, the 9th emperor of the Nguyen dynasty.

Ironically, this meritocratic selection process did not apply to the emperor himself and Khai Dinh turned out to favor French luxuries more than the welfare of his people. He raised taxes to please the French, and was not even popular amongst his own concubines, preferring to spend time with his male guard instead. Sadly we do not get to choose the emperors we serve under.

Even Khai Dinh’s tomb is all concrete and reflects his obsession with French modernity. It has aged badly in comparison with the Taoist, Buddhist-influenced architecture of the other emperor’s tombs. It lacks the perennially pleasing aesthetic of water, rock, and floating pagoda roofs opening up to the sky.

Our friend knows very little about her grandfather or the early life of her parents who were born in Hue, before moving to Saigon and then to the United States. In the photograph, Beetho’s grandfather appears calm and sports a beautiful little smile. I am yet to figure out what it is he holds in his right hand. Is it a scroll? But the end looks rounded and unlike a scroll. It actually looks like a tiny baguette even though that would be completely improbable. The robe is embroidered in characteristic clouds of colorful threads and on his chest is a fierce and teeth-baring tiger. The photograph has evidently been hand colored and the details are emphasized by the photographer/painter’s flourish with brush and paint.

Opposite him is a lady dressed in dark silks. I ask Beetho who she is and she guesses that it must have been her grandfather’s first wife. So this means Beetho’s grandma was one of his later companions. In fact, she was the third wife and she birthed Beetho’s father, who trained in classical music, taught it for a living, and later, nick named his daughter Beetho, after Beethoven.

Beetho’s mother who recently passed away is also commemorated with a photograph in her in-laws’ altar. Her luscious black hair offsets a beautifully round face. Beetho’s father is also present in another row, smiling, almost laughing, and radiant among his other relatives. Beetho beams and admires the photograph. She has never seen this particular one of her father’s.

The altars are bordered on the walls, by carved wooden tablets with what I presume are Buddhist scriptures. The script is often highlighted with gold paint and the tablets possess intricately carved frames.

We are ushered into a smaller adjacent room and soon a steaming hot meal is presented in front of us. Banh Nam Hue is a longish rectangle of rice and tapioca flour dough, generously spiked with a mixture of pounded shrimp, pork and onions wrapped in banana leaves and steamed. It is lusciously soft. There are also smaller banana parcels of steamed, clear glass-like rectangles of tapioca dough studded with a full shrimp within. This is Banh Bot Loc, another delicacy of the region.

The Banh Nam we have eaten till now in the restaurants at Hue have been admirable, but this particular batch is a notch above in its umami goodness. Restaurant meals can never stand up to the beauty of a home-cooked meal and I am so glad to have had this opportunity to eat this wonderful meal. The two silver-haired women smile and beam at us as we eat. I am all smiles. I manage to copy Beetho’s ‘ngon’(delicious) and tell them in between huge mouthfuls.

Our bearded friend, the elderly man in jeans, clearly seems to know a lot about the family history and is able to tell Beetho about when her grandfather resided in the house when he left for the city of Hue, and when her father lived here and where he slept (in another adjacent room). But Beetho’s Vietnamese is faltering and the same goes for our gray-haired friend’s English. She isn’t able to put forth the question ‘How did you know my father?’ to him. He repeatedly answers by mentioning the years in which her father stayed in the village house.

And hence we have no idea who the man and the two smiling women are. They all seem to know the loved ones in the photograph and mention who is who, so there is a huge possibility that they are Beetho’s relatives. We just don’t know how to ask them how they are related to her. They are absolutely kind and sweet and keep beaming at her. Clearly there is more going on than we can fathom. And this weird problem that we seem to have, only makes the whole interaction more endearing. After the meal we see the back rooms, and particularly one where there is an old cast iron four poster cot. We are told Beetho’s grandfather slept on it.

I walk around the rooms and take photos. I am trying to document as much as I can for Beetho. It is a relatively simple abode and is mostly commemorated only as an altar but the house is clearly cared for. White-washed walls gleam with borders of painted floral bouquets close to the ceiling. The floors are beautifully tiled with geometric patterns in cream, gray and black.

Satya and Arjun are out for a walk near the river. We decide it’s about time to say goodbye. We walk together towards the gate and cross star fruit trees copiously laden with fruit. Outside, the driver and I both take pictures of Beetho and her friends/relatives.

Something fascinating is taking place at the pier closest to us. There seems to be a hatchet that opens like a door to the wooden platform and a man on a boat is lifting and dropping bundles of green grass. I ask what it is meant for and am told it’s for fishing. Is the grass for the fish or are the platforms for fishing? I don’t know.

There is only so much that one can convey through language and even less when one doesn’t know the language but our few hours in Beetho’s ancestral home with people who care for it goes beyond language. We communicated entirely in smiles and beaming and it couldn’t have gone any better. Next time Beetho will bring her elder sister who speaks fluent Vietnamese and much of the haze will lift and she will have so much more to tell us about her ancestor’s past.

As we drive, the clouds look even more resplendent next to the mountains, the silver green river appearing to be a highway to its pinnacles.